“Safety Meeting”

The summer hiking season has definitely started with a bang here in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. On May 13, 2011 a bear mauling occurred in the Spanish Peaks Unit of the Lee Metcalf Wilderness Area, outside the northwest corner of the Park itself. The incident happened on a trail I’ve hiked frequently. The bear involved, a grizzly sow with cub, actually showed restraint in her measured response to the intrusion, but with two separate human fatalities occurring last summer on the opposite side of Yellowstone, again just outside the Park, it seems clear that bear encounters are an issue to be taken very seriously.

In the interest of safety for all who venture, or plan on venturing into the Yellowstone Wilderness, I’ve decided to do this newsletter on the subject of hiking and camping around bears. This is in no way a comprehensive guide to the subject of bear safety, however. Some excellent books have been written on the subject and I recommend all of them. Please see the “Recommended Reading” page of the YWM for a starter list.

I began backpacking as a boy scout. By the time I’d left home after graduating high school, my favorite hobby was traveling, often alone, through wild country. Accumulating the photos contained in the launch of this online magazine required over fifty backpacking trips in Yellowstone, most of them accomplished alone. In all, I’ve actually participated in over eighty backpacking trips in Yellowstone over the years, plus another couple dozen (so far) trips on surrounding National Forest, Bureau of Land Management and state lands. That makes over one hundred backpacking trips in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. In all these trips, there have only been a handful of problems, but those problems were real, and a few of them involved bears.

One reason bears remain such a threat is their unpredictable nature. This unpredictability arises from the intelligence of a creature with many options at its disposal. Bears are smart. Compared with other animals they surpass canines and are on a par with primates as far as sheer intelligence. Part of being a smart bear involves a healthy respect for humans, as a necessary survival tactic, most likely taught by the momma bear and instinct, as well as experience. Bears often appear as uncomfortable around us as we are around them. What this all boils down to is that bears generally don’t want trouble. What bears want is food and security and therein lies much of the problem.

The most recent bear attack involved a mother bear trailing along behind her cub while the cub chased an elk through a relatively low-elevation snow-free forest. Local wisdom, and I happen to agree with this, suggests that the bears were probably in that particular area due to prefered, higher elevation habitat still being snowed-in at the time, thanks to the well-above average snowfall the area received last winter. This drama unfolded not far from the Gallatin River and only a mile or so from U.S. Highway 191.

The hikers who were injured accidentally stumbled upon a situation where their presence interfered with the bears security needs. This appeared to be hunting class in full session and class was interrupted. This could not go unpunished because dealing with just such an intrusion was part of the lesson as well. It’s also worthy of note that the bear could’ve easily killed both hikers, but chose instead to give them each a bite they won’t soon forget. Both were able to hike out on their own, with a newfound respect for bruin motherhood one might assume. Neither person was carrying bear spray, which may or may not have helped since stopping an adrenaline-filled mother grizzly is somewhat like stopping a furry freight train. The “no guarantee” clause on the bear spray label is there for a reason.

Well, due to the fact that I learned about the mauling when I pulled into the trailhead to go for a hike and saw the bright orange ribbon indicating a closure strung across the trail, I quickly realized that this could’ve easily happened to me. These folks seemed to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. However, this does bring up the issue of how I hike and how I’ve been able to do this much solo hiking in a bear-filled ecosystem and live to tell about it. While I can’t claim to be an expert on bears or bear-human encounters, I’ve definitely seen my share of both.

Here are some tips for staying safe while hiking in bear country:

Be especially alert while hiking. It’s very important that you are able to see as much as possible at all times. Wearing a hat with a visor helps cut glare when the sun is directly in your face. Avoid the trap of constantly looking down at the trail when carrying a heavy load (trudging). While it’s important to watch for rocks, branches and the like that may trip you up, don’t get tunnel vision. Always keep one eye covering the woods around you. if you see a bear, or any wildlife that may pose a problem, you want as much time as possible to react. Bears are incredibly fast. To give you an idea, see the picture above? That bear could be on the photographer in about four seconds, maybe five at the most.

Areas of limited visibility hold potential for sudden, surprise encounters. For this reason, I sometimes choose to make noise in these areas. My preferred noise-making method is my voice, which can be quite loud and carries well through a pine forest for a distance of a hundred yards or so. Bear hearing ability is slighly better than ours, but can be affected by wind, nearby streams, etc. Don’t waste money on bear bells. I always see, or hear the voices of approaching hikers first, even if they are carrying bells on their packs.

Pay attention to the wind direction and combine that information with visibility at all times. Be aware that wildlife ahead of your direction of travel will be able to smell you if the wind is at your back, blowing your scent on ahead of where you are going. This, combined with good visibility, is what you want. When the wind is blowing in your face, it’s taking your scent back to where you came from, which does you little good. The worst hiking situation in bear country is poor visibility with the wind in your face. This is when I either make noise, or seriously consider waiting until a wind change or some other factor increases safety, if I’m in an area where bears are present, especially if I’m alone. When there is no wind present, hikers should proceed cautiously in areas of low visibility, as if the wind was blowing in their face.

Don’t hike alone. This falls into the ‘do as I say, not as I do’ category, but I have to say it. So I said it. But seriously, understand that there is no backup when alone and any accident, up to and including a bear attack, can lead to serious problems and put you into an instant survival situation. In the wilderness, there is safety in numbers. Because of this, the decisions I make in the backcountry when alone are often more conservative, with the emphasis on safety.

Hike slowly. Think about it. Slow hiking helps with keeping your senses alert. Follow the bends in the trail slowly. When you approach the top of a hill, take your time as you approach it. Stop and smell the roses, and for dead animals whose carcasses may attract bears. Breathe deeply the air of the wilderness, and don’t rush it. Plan your trip so that you don’t have to hike twenty miles a day, rushing to set up camp before dark and barreling down the trail like you wish you were on a mountain bike.

Don’t hike in the dark, even with a headlamp. Just don’t do it. Trust me. The adrenaline rush is not worth cleaning your underwear (or worse) when you see the eyes glowing on the trail ahead of you. Bears really do use man-made trails at night and travelling those trails in the dark alone or with one or two other people is asking for trouble. Bears seem to know that they have an advantage in the dark. Now, having said this, if you are part of a group of four or more people and are running late for some reason and must push on to reach a reserved backcountry campsite, or you are finishing your hike and returning to civilization, by all means carry on. Just don’t do it for the heck of it. At some point in the future I’ll do a newsletter detailing an experience I had after encountering a bear on a trail at night which was very unpleasant. Stay tuned. When hiking at night, I use a headlamp as well as a hand-held combination led flashlight/laser pointer, using both at the same time. I’m a walking light show, surrounded by wilderness. (Oh, there I go glorifying a dangerous practice. Shame on me.) Crossing streams at night, by flashlight, poses additional hazards and is another reason this type of hiking is not recommended.

Keep a clean camp. Don’t leave scented items or food in your tent at night. In Yellowstone, and the entire Greater Yellowstone backcountry, part of keeping a “clean” camp means hanging your food at night. Always do this as soon as you are finished preparing meals. Don’t wait until it’s dark to hang your food. Hanging a food bag in a dark pine forest, if a food pole is present, can be tricky. Hanging it adequately without a food pole in the dark can be darn near impossible. Don’t burn food scraps in a campfire. Garbage needs to go up with the food bag, double-bagged if possible. Because of the designated backcountry permit system in use in Yellowstone, it’s even more important that people keep very clean camps as they backpack in the Park. Leaving behind food scraps or bear attractants of any sort in a backcountry campsite could spell trouble for other backpackers who arrive at the site later, to possibly receive a visit from a food-rewarded bear coming back for more. If you are fishing, don’t clean fish near camp, and wash up good before you hit the sack.

Hike mid-day. Bears are most active at dusk, all through the night, and morning. Mid-day, especially in summer on hot, sunny days is often when bears rest in what are referred to as ‘day beds’. These are shady places in the forest where the bear has found or scooped out a shallow depression to curl up in for a snooze. This is exactly where you want them, unless you are hiking off-trail through thick forest, potentially disturbing their peace and quiet, in which case you’ll discover that bears are also very light sleepers, as luck would have it. They can even be awakened from near-hibernation stupors during winter. I prefer to hike along trails in Yellowstone between the hours of say, ten in the morning up until about three or four in the afternoon. Wake up time for resting bears seems to be about five, as they begin foraging for the evening.

Be aware that bears are more active on cloudy or overcast days in the summer.Use extra caution on those days.

Always carry bear spray and know how to use it. Be aware, by the way, that it’s useless in the rain and wind. It also expires, and the expiration date is real, not just a gimmick designed to sell more bear spray. Tests show the active ingredient, capsicum, actually does degrade with time, leaving a less-effective product. Replace it when the can expires and please participate in the bear-spray recycling program that’s been started around Yellowstone. We don’t need thousands of discarded bear-spray canisters piling up in our landfills. Also be aware that some bears have shown a tolerance to bear spray if they’ve been exposed to it previously. Remember, bears will endure numerous bee stings for a food reward-honey-so they are constantly balancing discomfort with survival, and often choose survival, or what they perceive as survival at that time, over a little discomfort.

Do not have a false sense of security because you have bear spray and/or a firearm. I’m not going to get into the handgun debate just yet. I’ll wait until a Park Service Ranger shoots an innocent, armed backpacker who was reaching for his water bottle (remember: you read it here first!) However, I will say that statistics show ‘playing dead’ is a much better defense, in the event of a surprise grizzly encounter, than trying to shoot the bear. Many bear attack victims have been armed, but were unable to get their weapon out in time to use it. Things happen very fast in bear encounters. If you rely on a gun for protection, you better have it very accessible and be very good with it, otherwise you are fooling yourself. You also must take into account that many bear charges are actually ‘bluff’ charges. Bluff charges don’t result in actual contact, but are merely a warning intended to scare the hell out of you. If a bear is shot during a bluff charge, it will naturally perceive the threat as real and most likely follow through with an actual attack.

Never camp in an area with recent bear sign, even if you have to change your plans. Trust me, the rangers will understand. Thanks to the innovative and very successful food-pole system implemented by the National Park Service, bears in Yellowstone seldom obtain food from humans. Because of this, it’s unusual in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to have a bear hanging around a backcountry camp which is occupied by people. If this ever happens to you, the bear is probably habituated to humans and may have lost its natural fear of people. This is more likely to happen with black bears than grizzlies, but either way, this is a dangerous bear and should be considered as such.

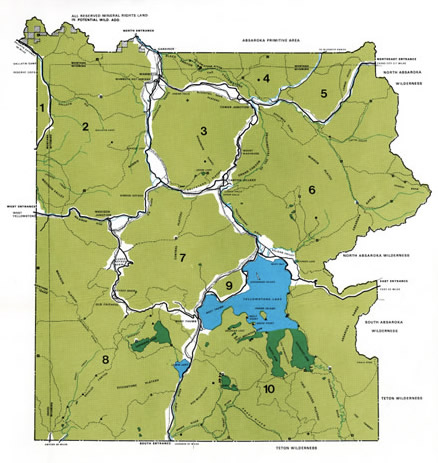

Obey all Bear Management Area regulations. These rules are in place for the good of both you and the bears.

Avoid cutthroat trout spawning areas in early summer. Cutthroats move into very small streams during their spawning season. This is why they are so vital to the ecosystem of the Park. Predators, including bears, can get at them very easily at this time. Because of this, avoid areas where cutthroats are spawning. This warning needs to be heeded from late May through the month of June and into July.

In the event of an actual bear attack, there are generally two types of attacks and two types of reactions you should consider. Attacks are usually either ‘predatory’ where, for example, a bear comes into your camp at night and begins messing with you or your tent, or ‘surprise’, where you come upon a bear, or bears, suddenly and they react by attacking rather than fleeing. As a rule, you should always fight back during a predatory attack, otherwise you are bear food. Statistics show it is also wise to ‘play dead’ during surprise encounters, indicating you aren’t a threat. Bears seldom consume people they have surprise encounters with. This is about security. Predation is about food. When you play dead, face down on the ground with your hands cupped behind your head, protecting the back of your neck. Hopefully you also have a backpack on to help protect your back, (and hopefully it weighs eighty pounds like mine does.) Often in this situation the bear will either leave the person alone entirely, or give a warning bite or slap to reinforce the point. Endure it quietly. During a recent bear mauling just north of Yellowstone, the female bear actually laid her head down next to the victim’s, while he was playing dead, for a full fifteen seconds, apparently testing him, while her cubs watched. After doing this, she took off with the cubs. The man, who was bow hunting at the time, survived after a brief hospital stay. He wasn’t carrying bear spray at the time of the attack.

Educate yourself. Read everything you can get your hands on about bears and their behavior if you really want to be the safest you possibly can.

Last but not least,always be willing to change your hiking and camping plans in bear country. Here’s an example of what I’m referring to. A couple of years ago I’d managed to get a few days off a busy early summer schedule and decided to do a backpacking trip starting out at Daly Creek, in Yellowstone’s far northwestern corner. My plan was to then hike out of the Park itself, going over Daly Pass and working my way back to my truck by hiking out Buffalo Horn Creek. The trip would be a pleasant two night, three day backpack into a great part of Yellowstone. After securing my backcountry permit I headed north to hit the trail and had the type of beautiful early summer day that we all long for in Yellowstone. The grass was green and plentiful, the scenery beautiful and I had the drainage all to myself.

I spent my first night at backcountry site WF2, broke camp and headed down the trail. That’s when I came upon bear scat. The scat was definitely large enough to indicate a grizzly and was only a couple of hundred yards from where I’d camped. The scat was fresh, obviously deposited during the previous evening, since it wasn’t on the trail when I’d walked a short way that distance upon first setting up camp. One pile of scat was flattened, as if being stepped upon, which sometimes happens as cubs follow along behind their mother, after the mother has defecated. There was no way to know a cub was around, however, without actually seeing it or seeing its tracks.

Taking all this into consideration, there was no real problem as long as the bear was following the trail back the way I came and not the way I was heading. I decided to look around for more tracks, which I soon found. They indicated that the next wildlife I was likely to see would be a large bear, since the tracks went the same way I was heading, which was up a thickly-forested, steep, rocky stream drainage high in the Gallatin Range, near the border of Yellowstone. Then the feeling came. That semi-nauseous, mild vertigo type feeling I get when emotion runs to my brain telling me that I’m not safe. What this scenario amounted to was that at least one large bear, likely a grizzly, was heading up into the same exact area that I was going. While it was entirely possible that the bruin would be off in a day bed sleeping as I continued my hike, that was only one of many places it could possibly be at that time. Another possibility could be right off the trail, just over a rise and out of sight until it was too late to avoid an encounter. Besides the tracks affirming the bears presence, the wind was also blowing in my face, taking my scent back to where I’d already been, not to where I wanted it, which was ahead of me. Additionally, I was alone, with no one to get help in case of a problem.

This was a dilemma and I turned around. The rest of the trip consisted of my leisurely hike back to my truck, in the opposite direction of the bear. Why? The answer is that I had freedom of choice and I chose safety as the number one priority, which meant a change of plans. Sure, I could’ve been a reckless stud and proceeded, yelling all the while and jumping at every little sound, but for what purpose, a great day in the Park? I wasn’t on a thousand dollar photo assignment, I was enjoying my days off. So, I decided to experience the Park another day, when I’m not sharing a stream drainage with a griz, thank you very much. While I’m confident that my bear spray works and is a good product, I’m not overly eager to test it in a real-life situation.

This, my friends, is called using your head in grizzly country, and not behaving as if the backcountry belongs to you and you alone. This is the bears home. Why intrude, if you have ample evidence that there are bears nearby whom experience has shown us would rather be left alone? Now, do I cut the trip short every time I see a bear track? Of course not. These were unique circumstances which warranted a decision. I erred, perhaps, on the side of safety, which is the only way to err. As a result, I’m here to write these wonderful newsletters for people worldwide who are interested in seeing beyond the surface of Yellowstone! Hooray!

It’s also important to keep things in perspective in Yellowstone, as far as safety goes. Backpacking in this Park is not the most dangerous sport around. What about extreme backcountry skiing? Kite skiing? Mountain climbing? Riverboarding the Gallatin River at 6100 cfs? Have you been to the rodeo in West Yellowstone? I think you get my point. Most likely, the drive to Yellowstone will be the most dangerous part of your excursion.

So, be flexible and conservative with your backcountry plans. Use your head. Look for wildlife sign constantly and make that an exciting, educational aspect of your experience. Know which way the wind blows and make noise only when you should. Keep a clean camp. Have your bear spray handy and get on with it. Summer goes by fast. Happy trails.

Patrick Wherritt, Jr.

Publisher

YellowstoneWildernessMag.com