“THE STATE OF THE BACKCOUNTRY”

A mixture of pride, concern and hope accompany this, the first newsletter of the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag. The pride comes from seeing this project finally come to fruition. The concern arises from the current ecological state of certain areas of the Yellowstone backcountry, and the persistent influences affecting this region, both ecological and political. The hope exists as a result of seeing the Yellowstone Wilderness endure beyond past challenges to it’s present condition with all the biological pieces still in place, along with a framework of laws designed to carry it well into the future, if only those laws are followed.

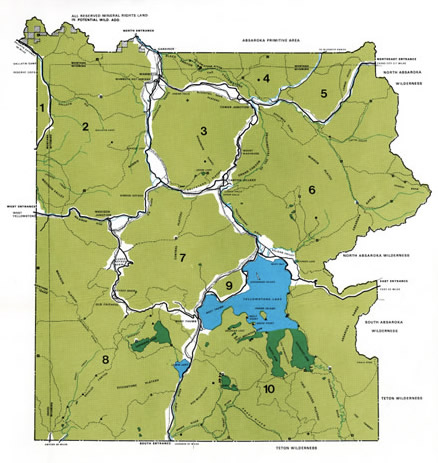

Yellowstone, the world’s first National Park, was established in 1872. Since then, many events have occurred, such as the removal, then later the restoration of large predators, the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964; the success of Yellowstone’s Bison recovery; and the fires of 1988, which greatly affect the Park’s wilderness. As we launch the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag, perhaps it’s appropriate to take an honest, direct, comprehensive look at the Yellowstone backcountry, to take stock of it’s current condition.

As Yellowstone approaches the ripe old age of 140, an array of threats apparently stand ready to alter the future ecological health of its large wilderness areas. These threats, some of which have been around for decades, arise from a variety of sources and weave a complex portrait of Yellowstone, a huge preserved natural area struggling to maintain its ecological integrity while facing the realities of today’s changing world.

The list of threats is significant. While Yellowstone now hosts an age-diverse, vigorous forest emerging after the fires of 1988, two insect species, the spruce budworm and the pine bark beetle, plus a fungus commonly referred to as blister rust, are already impacting thousands of acres of Yellowstone forest. Whitebark pine trees, whose nuts provide an important late-season grizzly bear food, have demonstrated susceptibility to both blister rust and the pine bark beetle. Whitebark forests, as a result, are now showing signs of large-scale die-off. Some estimates foresee an eventual loss of as much as 85 percent of these forests in the near future, which is not good news if you’re a grizzly bear doing long-term family planning.

Also affecting Yellowstone’s backcountry flora health is the issue of bison grazing, and the American Bison population situation in general. While no one argues the point that bison belong in Yellowstone, there is serious ongoing debate as to whether or not forcing a few thousand head of bison to sustain themselves year-round within the man-made rectangle of Yellowstone’s boundaries is causing adverse affects upon Park vegetation. Would all this grazing occur under more natural conditions, for example, if the bison were allowed to migrate in and out of the Park, as their natural instincts lead them to do? From a wilderness perspective, suffice it to say that a backcountry traveler in Yellowstone would most likely encounter many more bison in the Park’s backcountry today than they would have in pre-settlement times, because Yellowstone is the only place left where these animals can exist and thrive. Therefore, we have a slightly different Yellowstone Wilderness than existed before Yellowstone became the home of last resort for these bison. This, of course, begs the question, “How many bison in the Park is too many?” The answer to that question ends up being a value judgment, one way or another.

Another issue directly affecting the Park’s backcountry which ultimately falls on society’s value judgment, is the role of hunting in controlling and influencing Yellowstone’s elk population. This gets more complicated when factors like wolves, the disease brucellosis and human poaching are thrown into the mix. (For more on this particular subject, see the “Recommended Reading” page and Gary Ferguson’s book, “Hawk’s Rest”.)

Indeed, managing public lands in America today often involves compromising between different user groups, and Yellowstone certainly has a very interesting mix of these. When it comes to elk, many voices insist on being heard, and one can’t help but wonder what the elk are really there for, anyway. Are they there strictly to serve the purposes of those who would benefit economically from harvesting them? Or do they have another purpose, involving the ecological health of the entire region?

These issues touch on some of the true conflicts of Yellowstone management which comes down to who really has the power. Is it private enterprise, in the form of outfitters, hunting guides and concessionaires, or is it “we the people,”- and our publicly owned wildlife herds? This becomes a very interesting and complex question indeed, since “we the people” also means “we the hunting guides”. And make no mistake here, folks, hunting may not occur legally within Yellowstone’s boundaries, but hunting opportunities outside Yellowstone are a factor influencing many Yellowstone wildlife decisions. Those elk herds are a valuable economic asset to the surrounding states of Montana, Idaho and Wyoming, since hunting dollars and the associated travel revenue bring in millions of dollars annually.

Speaking of valuable economic assets, Yellowstone’s many fish also come to mind, and on that subject there is one large dose of very bad news. One of the saddest situations in Yellowstone today is the decline of native cutthroat trout in Yellowstone Lake due to the introduction of non-native “Mackinaw” or “lake” trout, which are native to the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern U.S. These lake trout have no natural predators in Yellowstone Lake and feed voraciously on the Lake’s native cutthroats. Biologists estimate a full-grown lake trout will eat more than 2,000 cutthroats in its lifetime.

While this topic alone could easily fill a book, it’s important to at least understand that this loss of cutthroats has seriously impacted the biological health of the Yellowstone Lake ecosystem. Forty-three species of birds and mammals in Yellowstone feed (or fed) upon the Lake’s cutthroat trout. Until the non-native lake trout were discovered, Yellowstone Lake was considered the Rocky Mountain’s largest, finest pure cutthroat fishery. That’s all changed now. Some spawning streams which used to host fish by the thousands now see few fish, if any at all. It’s not that the cutthroats are gone entirely, they just appear to be a remnant of what they once were, and so only a remnant of the birds and mammals that once fed upon them are now visible in the Yellowstone Lake area.

This is heart-wrenching to those who knew the historic cutthroat bounty of this lake. Because this is such a serious issue, the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag advocates excluding most of Yellowstone Lake from future wilderness designation, simply because we feel that Yellowstone’s fishery managers should have every available tool possible to deal with this invasive lake trout problem. Gill nets used to remove the lake trout require motorboats, so the compromise, we feel, is worth the result, as the cutthroats are essential to what’s left of the Lake’s ecosystem.

Moving on to new threats, but still staying in the water, we have two more exotic species to contend with in Yellowstone’s backcountry: zebra mussels and New Zealand mud snails, both most likely transported to Yellowstone accidentally by fishermen. The net result is a loss of aquatic trout habitat and, eventually, waterways that support fewer fish, which therefore feed fewer birds and mammals. So far, areas primarily affected seem to be front-country areas of the Madison River system, yet invasion into backcountry rivers and streams by these organisms is a very real probability and could ultimately spell more bad news for Yellowstone’s cutthroat population.

Other influences outside Yellowstone’s boundaries also threaten to chip away at Wilderness biological health. Most notable are recent proposals for new natural gas wells in the Bridger-Teton National Forest, just south of Yellowstone. Between timber sale proposals, mineral rights, private property rights and motorized use access, issues are always coming up in the Yellowstone ecosystem which deserve pragmatic, albeit complex solutions. (If you would like to know more about any of these current ecosystem-wide issues, please see the Greater Yellowstone Coalition website on the “Links/Friends” page.) Add to this the uncertainties of long-term climate change and everything that involves, plus a U.S. Congress which has so far failed to follow the mandate of the Wilderness Act of 1964, and you have an overview of some of the more negative current influences upon the Yellowstone backcountry.

The news, however, isn’t all bad, as wilderness proves to be a resilient force, especially when empowered by an adoring public in an effective democracy. Many events in Yellowstone’s recent history have proven very positive for backcountry ecological health. We can go as far back as the cessation of the Park’s war on predators to see the beginnings of a trend towards positive change. The Park’s “Let It Burn” policy, a necessary and natural evolution of fire management in Yellowstone, which most agree was allowed to go as far as it should have in 1988, also ended up being good news for the Park’s backcountry . The science of managing (or not managing) large tracts of wild land as islands within the sea of modern America has had no choice but to learn from its own mistakes. Were fires allowed to burn in the Park from the beginning of its establishment, they certainly wouldn’t have been as large as they ended up being in 1988, with so much more fuel available. Anyway, the long-term benefits of the fires are now clearly visible in many areas of Yellowstone, and the Park is home to a reinvigorated forest, which hopefully is large and healthy enough to stand a chance against the climatic and biological changes of the future.

We can also count that magnificently troublesome beast, the American Bison, among the Park’s backcountry good news. Too many bison for a limited area of land is undoubtedly a preferable situation than, say, no bison at all. Hard as these bison are to confine, manage and re-distribute around the U.S., Yellowstone’s backcountry wouldn’t be the same without them.

Similarly, the Yellowstone grizzly bear population, thanks to a number of factors, continues, for now to be a success story. This not only greatly enriches the backcountry experience, but also is a somewhat positive indicator of Yellowstone’s wilderness health. The National Park Service in Yellowstone, along with the U.S. Congress and the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the States of Montana, Idaho and Wyoming all deserve some credit for this current, and I stress “current,”- grizzly population recovery. It’s also important to recognize that much of this success has been achieved merely by following the advice of pioneering grizzly researchers, like the Craighead brothers. Cutting the bears off from human food sources, establishing large backcountry “Bear Management Areas” and putting the grizzly on the Endangered Species List are a few of the actions that have, most likely, saved the grizzly in the Yellowstone Wilderness.

As previously mentioned, the decline of cutthroat trout in Yellowstone Lake has undoubtedly sent shock waves throughout the ecosystem, but, the evolution of Yellowstone National Park fishery management that has developed largely as a result of facing such challenges has been a very good thing. Early Park visitors dined upon native fish at will, completely unregulated, while non-native fish were being stocked in many Park waters. Today, Yellowstone operates under an enlightened policy which largely favors native fish, and attempts to restore them to as much of their original waters as possible, as well as any other Park waters that are appropriate. While many of Yellowstone’s streams were historically fishless, primarily due to geographical barriers, we can be proud of today’s Yellowstone backcountry fishery, which, barring unforeseen circumstances, should perpetuate itself far into the future, excepting, of course, the tragic situation at Yellowstone Lake.

Even though the ongoing snowmobile drama plays out primarily on Yellowstone’s road system, the Park’s backcountry is undoubtedly better served by recent National Park Service Winter Use Plans which place limits on snowmobile numbers and require snowmobiles used in Yellowstone to be the new cleaner, quieter 4-stroke models. The older snowmobiles could be heard far into the backcountry, and that noise is largely gone now. So too is the blue haze that used to hang over the Park entrance at West Yellowstone on winter mornings during the days of unlimited 2-stroke snowmobile use. We can cautiously put the snowmobile situation into the “Challenges Overcome” category-and call this a victory for the backcountry as well.

Now, a few words about wolves. Regardless of how one feels about the animal, the return of the gray wolf to Yellowstone has been a remarkable success story and an excellent example of an ecological void being quickly filled. Plenty of data is beginning to emerge showing numerous subtle changes taking place in the Yellowstone ecosystem as an apparent result of wolf reintroduction. Most of these changes appear to be beneficial and generally focus around an increase in riparian habitat caused by elk movement away from these areas.

Other interesting changes have been noted as well, such as a decrease in coyote populations around wolf packs, which led to an increase in foxes, of which wolves are apparently more tolerant. In fact, the “wolf effect” continues to ripple throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem-and beyond, fifteen years after the wolf reintroduction took place. And so the story continues, both ecologically and politically. How wolves, along with Yellowstone’s other more controversial wildlife, fare outside the Park’s boundaries is another chapter altogether. Wolves, like grizzlies, fit in just fine in the Yellowstone Wilderness, but is society ready to accept them on the outskirts of Pierre, South Dakota? Probably not.

What’s interesting about many of these issues is that whether “positive” or “negative” — they often depend upon one’s point of view. The actions taken against bison when they decide to leave the Park during harsh winters tends to polarize people politically, as do many bear management concerns and the wolf issue as well. Even the presence of mackinaw trout in Yellowstone Lake, if one is a mackinaw trout fisherman, could be seen as a good thing-from a personal perspective. I know of one individual-who resides in Gardiner, Montana, on the north edge of Yellowstone, who fancies himself a fishing guide. He also advises his clients to kill cutthroats they catch on the Yellowstone River, just outside the Park itself, and return the non-native rainbow trout they catch back to the river. When I asked him why, he replied, “The rainbows jump, they’re funner to catch.”

It seems that we, as a culture, ultimately see Yellowstone much the same as we see many other things—through the prism of our own beliefs and desires.

Is Yellowstone empty, as Yellowstone Lake seemed to be one recent summer evening, as I gazed upon Mary Bay-hoping in vain to see a single cutthroat rise? Or is Yellowstone full, even bursting at the seams, as its bison population seems to suggest?

It turns out that the state of Yellowstone’s backcountry is largely a matter of perspective.

Welcome to the Wilderness Perspective!

Patrick Wherritt, Jr.

Publisher

Yellowstone Wilderness Mag