“WHY YELLOWSTONE NEEDS WILDERNESS DESIGNATION”

As someone who has an appreciation for American history, I’m pleased by the enormous popularity of the Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. I’m also disappointed that, with such a fine, detailed published record of the resource abundance of the American West so frequently read, more Americans don’t look around at what remains of this landscape and ask the question -“What happened?” Granted, certain pockets of the West, such as the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, have retained their biological wealth, but most of the West, the vast majority of it, has been denuded. Settled. Fenced-in. Tamed. Churched-up. Gone are the vast herds. The mountains are still there, of course, but we now search for their elusive, wild heart, the same heart that Captains Lewis and Clark so deliberately and thoroughly entered.

Many others also entered this wild heart of America, making names for themselves. Men such as Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, Jim Bridger and even John Colter were held in high regard for their strength of character and legendary wilderness adaptation skills. Going back even further than the story of Lewis and Clark, we know also of the great wilderness that greeted the pilgrims as they landed the Mayflower on the Eastern seaboard. This relationship between the landscape of the United States and the character of our nation, in fact, has been deemed so vital to the strength of our Democracy, for so many basic reasons, that we’ve actually passed legislation intended to preserve real wilderness within our nations borders permanently. This wild heart of America was viewed as so valuable it was thought that it must be preserved as a resource from which we could draw upon in the future, for our very nourishment as a culture.

One could argue that this process of recognizing and ultimately legislating, on a national level, our need for wilderness preservation actually began with the creation of Yellowstone National Park itself. Wherever it began, this idea of wilderness as a national necessity came into its own with the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964. This law required all agencies which manage public lands, The National Park Service, National Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, to evaluate roadless areas of 5,000 acres or more, within their holdings, for inclusion into a National Wilderness Preservation System. Once included in this system, lands would not be legally available for future development of any kind, including road-building and resource extraction, thereby protecting them forever, in addition to whatever legal status these lands may already have as National Parks, Forests, Monuments or Wildlife Refuges. (The entire text of this legislation, by the way, is downloadable on the “Laws Regarding Yellowstone Wilderness” page of the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag.)

Since its passage, this act has officially and permanently set aside over 109 million acres of publicly-owned American land from all development. These 109 million acres unfortunately were not found in one enormous, connected unit, but are a combination of all 757 different Designated Wilderness Areas located in 44 of the 50 United States and Puerto Rico (2010 figures). These areas vary in size from 6 acres (Pelican Islands Wilderness, Florida) to 9,078,675 acres (Wrangell-St. Elias Wilderness, Alaska).

While it’s a commonly-held belief (at least in the lower forty-eight states, Alaskans know better!) that Designated Wilderness Areas are made up only of National Forest lands, the National Park Service actually has the highest percentage of it’s land, 56 percent, designated as wilderness. This fact reflects the mandates of both the National Park Service, which seeks to preserve areas “unimpaired for future generations” and the Wilderness Act, which intends to preserve land in a state “untrammeled by man”. When one takes into consideration the fact that human population growth shows no sign of slowing down, it becomes obvious that visitation to as well as pressures upon existing wild areas will only increase in the future. Add the fact that the resource base of actual wild, undeveloped land is continually decreasing, due to urban sprawl, resource development, etc. and it becomes evident that if we are to receive the full intended long-term benefits of the Wilderness Act, we need to follow-through and designate ALL intended lands, especially National Park lands that qualify, as wilderness. We need this quite simply because we can’t create new wilderness, and we don’t really know how much wilderness we may need in the future.

When it comes to designating wilderness in National Parks, the issue has already been dealt with in many of them, but not in Yellowstone. Yet, there are many reasons why the backcountry of Yellowstone should be at the top of the list for wilderness designation. First and foremost is the ideological argument that Yellowstone, being the world’s first National Park and the model for all others, should be at the forefront in complying with all required legislative mandates, the Wilderness Act being one of them.

Second is the sheer value of the ecological completeness of Yellowstone, and the need to preserve it. It’s important to remember that no other National Park in the lower forty eight United States has every single wildlife species present before the white man came upon the scene, including a free-ranging buffalo herd, although they all intend to preserve wildlife and wildlife habitat. When one looks at the list of National Parks in America it becomes obvious that many are in a seriously degraded condition-as far as the biology of the large mammal populations. Many of these Parks were designated long after the top predators were extirminated and many other species were knocked down to remnant populations. Yet, many of these National Parks, particularly those in California and, for example, the Olympic National Park in Washington and Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado, have had their backcountry already designated as wilderness. It’s time to do the same with the most complete Park in the lower forty-eight states, the world’s first National Park-Yellowstone.

Third, no user group is left out by designating Yellowstone’s backcountry as wilderness. Snowmobiles are now, and always have been allowed to operate only on Park roads during winter, not in the backcountry. Mountain bikes are presently not allowed in most of Yellowstone’s backcountry, nor are there any plans to significantly increase mountain bike access to Yellowstone’s backcountry, regardless of wilderness status. Other forms of motorized transportation are not presently allowed either, so no one who has access to the Park backcountry before wilderness designation will be denied access once wilderness designation takes place.

Fourth, the natural resources of Yellowstone’s backcountry, with one exception, are not available for development. No future timber or mining rights are in danger of being lost. Private property issues affecting wilderness designation are virtually non-existent. Therefore, the usual opponents to wilderness designation, corporate lawyers, are largely absent in the debate concerning National Park Wilderness. Now, the one exception I mentioned above is actually a rather large one and one that needs to be closely monitored in the future. That exception, the one resource which is presently harvested in small amounts and studied intensively in Yellowstone, is the microbiology of the Yellowstone thermal features, both frontcountry and backcountry, in which science, and pharmaceutical companies, are very interested. These thermal features have already been found to contain organisms that are extremely valuable to science. One, the heat-loving bacteria ‘thermus aquaticus’, is used in the polymerase chain reaction DNA amplification technique. That’s a rather technical way of saying this bacteria is used in a particular type of DNA identification. That’s pretty important stuff for an organism found thriving in an obscure Yellowstone hot spring. It also makes one wonder what else might be out there, given that Yellowstone contains such an incredible array of thermal features, many with their own unique microorganisms.

Pharmaceutical companies, therefore, definitely have an interest in legal matters concerning access, public royalties, etc. involving these thermal features and the largely unknown microbiology they contain. This stands as the fifth reason to designate Yellowstone’s backcountry as wilderness-big pharma now has an interest. We also need to preserve forever the wilderness settings these potential biological treasure troves are found in. Thermal features located near roads in Yellowstone, such as Morning Glory Pool (pictured) are frequently vandalized by Park visitors. Morning Glory Pool, in fact, has experienced a lowering of its water temperature as a result of coins and other objects being thrown into it and partially plugging its underground plumbing. This has actually altered the microbiology of the pool, even changing the appearance of the pool itself. Continual efforts must be made by National Park Service staff to remove litter, etc. from many thermal features located near roads. On the visit to Morning Glory Pool to take this photograph, a gift shop receipt from nearby Old Faithful Inn was found floating on the edge of the hot spring. I had to remove it with a dead branch to obtain this image. Issues concerning the future of backcountry thermal features in the Park all indicate a need for a level of physical protection for these resources while we carefully study their unique molecular biology. Wilderness designation of lands surrounding such scientific assets is a way to increase security for these areas without the ridiculously obtrusive use of backcountry surveillance cameras, which the Park Service has now put us on notice they intend to use (see “Is Big Brother Heading for Yellowstone National Park’s Backcountry?”, News and Articles page).

Sixth reason? The American Bison and the hazing which presently takes place during severe winters as bison attempt to leave Yellowstone to seek grass at lower altitudes. Although the National Park Service insists snowmobiles and all-terrain vehicles do not cross into Yellowstone when hazing operations occur, they readily admit that low-flying helicopters are often granted permission to violate what is technically “de facto” wilderness airspace to perform these operations. This hazing solution to the problem of bison leaving Yellowstone is in no way a long-term answer and remains a temporary, questionable management tool at best. If Yellowstone’s backcountry is designated wilderness, such tools would be less of an option than they are today. At that point hopefully the governmental agencies involved can begin, out of necessity, to manage the bison the same way they manage other wildlife, which prioritizes habitat while taking into account hunting and predation pressure. Wilderness designation is an obvious component of any possible future bison solution.

The seventh reason for wilderness designation in Yellowstone would be the fact that, as Park visitation continues to increase, demand for Park services and visitor amenities often does as well. Increased demand often leads to increased development. In other words, people are enjoying Yellowstone in bigger and bigger numbers practically every year. This fact gives those who manage Yellowstone’s visitor services a ready excuse for more development, which is what concessionaires continually want and are eagerly waiting for. With no legal limitations placed on road-building, where does this all end? Limitations must be made on which areas of the Park are open to future development, and the backcountry must be officially and permanently placed off limits. Once again, the only way to do this, the mechanism placed within our framework of laws for just such a situation, is the Wilderness Act, which should be legislated in this National Park.

The eighth reason to designate Yellowstone’s backcountry as Federal Wilderness is simply to make certain that, regardless of future political situations, there will never be a possibility of developing the Park’s backcountry. The ONLY way to eliminate all future possible development is through wilderness designation and the Wilderness Act of 1964 clearly intended the backcountry of Yellowstone, as well as all other National Parks, be Designated Federal Wilderness. This battle has already been fought and won, we are just asking that the victory be legally enforced.

A ninth reason to finally put into place Yellowstone’s rightful wilderness designation is to halt the endless naming of natural features in the backcountry, thereby preserving an essence of discovery and wildness. Much has been made of a guidebook published a few years ago which took it upon itself to name some previously unnamed Yellowstone features. The United States Board of Geographic Names (USBGN) does not recognize new names of natural features within Designated Wilderness Areas, although it does recognize new names of features within National Parks that aren’t Designated Wilderness. Therefore, for those who wish to see features in the Yellowstone backcountry remain nameless, the only long-term answer is wilderness designation.

For those whom are rightfully concerned about management issues in Yellowstone such as firefighting, wilderness rescues and the invasive lake trout problem in Yellowstone Lake, rest assured that wilderness designation would not mean that the Park’s forests will be left to burn next time a conflagration occurs. Nor will Uncle Henry be left to die if he gets himself into a situation requiring motorized rescue in Yellowstone’s backcountry. The Yellowstone Wilderness Mag also supports Park Service proposals leaving most of Yellowstone Lake out of wilderness designation in order to facilitate managing the lake trout problem.

The biggest day to day management challenges after wilderness designation would most likely fall upon the Park’s trail crews, which would be limited in the types of motorized tools available for their use while maintaining Yellowstone’s over one-thousand miles of hiking trails. At present, chainsaws are used sparingly, only in areas where fallen trees are extremely heavy and usually only by Park Service Rangers opening trails up early in the summer season. The Bechler area, with little forest fire burn overlapping trails, has been able to operate without chainsaw use on trails since 2006. The Park Service also maintains a collection of tools to clear trails manually. The Park Service, as well, readily admits that most present chainsaw use is done to accommodate stock use. The Yellowstone Wilderness Mag would like to politely suggest that, if more physical labor is required to clear trails manually after wilderness designation takes place, perhaps those who benefit most from chainsaw use-the stock users-should fill the gap on this labor. Regardless, the ability to use chainsaws for trail clearing should not be used as a reason to prevent Yellowstone’s backcountry from being designated wilderness. Chainsaws are a modern tool of convenience, not an absolute necessity for trail maintenance. In fact, once this designation takes place, the forest will be quieter, as chainsaws would be silenced.

At this point, I’d like to bring to the reader’s attention that two highly reputable conservation organizations, Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness and the Wyoming Wilderness Association, presently favor designating Yellowstone’s backcountry as wilderness. Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness has been formed for the sole purpose of seeing the Gallatin Range protected, and their excellent Gallatin Wilderness and Wildlife Conservation Area Proposal includes the Gallatin Range within Yellowstone, as well as much of the range north of the Park itself. (Please read more about both of these groups by clicking on their websites, which can be accessed on the “Links/Friends” page of the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag).

Now, I’d like to pose a question to our readers. Can anyone out there, other than the ranger who has to clear the trail to the Thorofare cabin, think of a reason to not designate Yellowstone’s backcountry as wilderness? Can anyone out there come up with even one good reason? I didn’t think so. And if wilderness designation were not necessary, as Park Service officials in Yellowstone often like to say, then why has 56 percent of all National Park land been designated as Federal Wilderness so far?

So, who is it who is against designating the backcountry of Yellowstone as Federal Wilderness, and why hasn’t it been done yet?

The answer to both of those questions is the U.S. Congress.

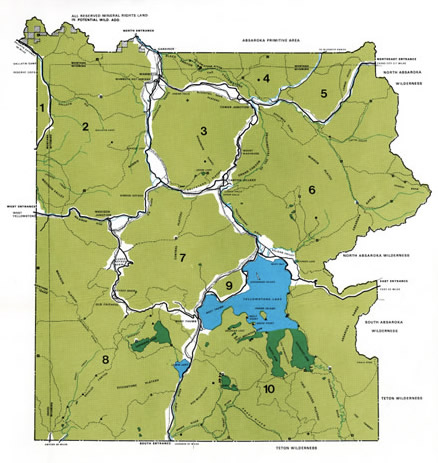

In order to designate the Yellowstone backcountry as wilderness, a bill must be passed through both houses of Congress, and signed into law by the President, just as for all other wilderness areas. While the Wilderness Act got the ball rolling on this issue as far back as 1964, nothing has yet been done, beyond Yellowstone staff mapping and numbering proposed Wilderness Areas. Yellowstone National Park Staff even completed Wilderness recommendations in 1972, only to have those recommendations thus far ignored by Congress. Its also worthy of note that Yellowstone officials, well aware of their obligation to uphold the Wilderness Act mandate, always maintain an individual with the title of “Wilderness Coordinator” available to answer questions on the subject of Yellowstone Wilderness Designation, thereby giving credibility to an issue which Congress chooses to ignore. Since Yellowstone sprawls across a geographic area overlapping three states, congressional support for its wilderness designation would, in all reality, have to be secured by at least one or more of these state’s Congressional Representatives. The bill could be introduced by anyone, but for it to pass, some support from the states of Idaho, Montana and/or Wyoming would be necessary. At this time, with Republican anti-wilderness politicians holding most seats from these states, chances are slim for such support. This fact underscores how important this wilderness designation actually is, for there are people who definitely don’t want it, and they are quite powerful.

Sadly, even Montana’s Democratic Senators Max Baucus and Jon Tester have publicly stated they are against wilderness designation for Montana’s Glacier National Park, even though that Park’s own Superintendent has spoken out in favor of such designation. (See “News and Articles” page of Yellowstone Wilderness Mag for more on this topic). Since this wilderness designation would be taking place on land already designated as a National Park, one has to wonder why U.S. Senators would be against such designation. Could there be future development plans already in the works? Or, is wilderness just such a forbidden topic among powerful supporters that it must not be valued, no matter where it is found? These are questions that need to be answered. The public deserves these areas be designated wilderness, as the law intended. It is the public’s right to have the Wilderness Act upheld.

As I write this, I’m struck by the realization that few things on this planet remain all that they are rumored to be. Yellowstone remains one of those few. And, within Yellowstone, we have that one commodity in life which is all things to all people-real wilderness. Think about it for a minute. To hunters, it is a safe-haven for the wild game they covet so relentlessly. To the fisherman wilderness contains the waters which promise their pastime will be enjoyed by not only their children, but their children’s children. To the hiker, wilderness itself is both the means and the end to a complete recreational experience. Even to the very spiritual, wilderness is a place of quiet and refuge. Indeed, whether one is a skier, writer, photographer, birdwatcher, painter, scientist or just plain wanderer, wilderness holds the raw material in life you are looking for. It is the one thing that is all things to all people. It is one thing your children deserve.

What better exemplifies wilderness in today’s world than Yellowstone National Park? If any of this makes any sense to you, the reader, please consider reading the “How You Can Help” page of the Yellowstone Wilderness Mag, and perhaps sending an email, or better yet a hand-written letter, to one or more of the members of Congress listed. Also, please support the Wyoming Wilderness Association and Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness as well. If there is still a wild heart of the Rocky Mountains in America, it is this collection of wildernesses that make up Yellowstone. Please help us ask Congress to do its job by following through with the Wilderness Act, protecting these areas forever.

Patrick Wherritt, Jr.

Publisher

Yellowstone Wilderness Mag